In his introductory comments at the 2014 Griffith University Tony Fitzgerald Lecture, Tony Fitzgerald – the former Chairman of the Commission of Inquiry into Official Corruption in Queensland – singled out News Limited’s Queensland tabloid newspaper, the Courier Mail for special criticism.

“I’m now about to adopt my grumpy old man persona … I have decided that I have to say something beyond that [a note he wrote in the printed program – see below]. Knowing that observations of mine in tonight’s program will again irritate the Murdoch media especially Queensland’s own Courier Mail, which would be better called The Craven Mail because all bullies are cowards.

The Craven warrants a special mention for its pompous self-regard and gutter tactics. It’s decent journalists must find it unsettling to work alongside rabid gossip-mongers and an editor who has made the paper an object of derision for thinking Queenslander’s by virtue of its debased tabloid standards and blatant pro-government and anti-intellectual bias.

A compulsion to harm someone whom you’ve never met because you dislike his opinions but can’t rebut them, suggests a disturbing pathology.

Last Saturdays’ edition of The Craven contained another rambling smear under the heading “Fitzgerald Failures Hit Nerve”. The simple purpose of that inane statement – under the heading “Fitzgerald Failures Hit Nerve” – was to highlight the key slur, “Fitzgerald Failures”. The turgid content of the article includes a favourite Murdoch media theme – its’ self-perceived superiority – plus a truly momentous revelation of my failure by an acquaintance of Queensland’s recently-appointed totally unsuitable Chief Justice.

According to The Craven, its source – a retired journalist – conveniently told it that he, and another retired journalist, disagree with some of my decisions during the corruption inquiry. When my attention was drawn to this, for I don’t read the Courier Mail – The Craven – it felt, to adopt former Prime Minister Paul Keating’s graphic phrase, ‘like being flogged with a wet lettuce’.

Since the inquiry concluded 25 years ago it seems that The Craven’s informant thinks and acts quite slowly. The compelling reasoning which underpins his lethargic opinion can be discerned in his tragic lament: “I gave Fitzgerald transcripts of phone taps on who ran what in organised crime in this country, he didn’t pursue it, he never even looked at it as far as I know.” Precious. That, and other self-focussed drivel, provided The Craven’s malicious hypocrites with a spurious foundation for their latest spiteful ambush.

The hatred and lies of those whose criminality, misconduct and incompetence I exposed, their fellow-travellers and lackeys, and miscellaneous far-right lunatics and conspiracy theorists, have continued since the corruption inquiry. It diminished to some extent after 1998 when I retired as President of the Queensland Court of Appeal and left the state for a period.

But it has built up again following my public opposition to the current government’s attempt to reverse the post-inquiry reforms and return the state to its previous dark era. I’d prefer to disregard the abuse but I don’t want my silence to encourage bullies like The Craven or discourage others, especially young people, from speaking out against powerful vested interests. The Craven’s strident partisanship provides a useful reminder to any who might be interested that any possibility of effective democracy will be lost if we allow ourselves to be intimidated and silenced by reactionary self-interested politicians and media riff-raff.

I feel better now … ”

————–

It is not because a part of the government is elective, that makes it less a despotism, if the persons so elected possess afterwards, as a parliament, unlimited powers. Election, in this case, becomes separated from representation, and the candidates are candidates for despotism.

The Liberal National Party was elected in Queensland, with a huge majority, in March 2012. Coincidentally, a few days later, Professor Hilary Charlesworth, the distinguished feminist international law scholar, delivered the previous lecture in this series.

The following brief passages are taken from my remarks introducing Professor Charlesworth that night:

“…Queensland recently overwhelmingly rejected another failed government and elected a new group of politicians with ambitions which, if history is a guide, might exceed their talents and experience.

A pessimist – perhaps even a realist-might expect the new government to choose business as usual, followed by electoral rejection in due course, and the cycle of public disappointment to continue. However, the magnitude of the government’s victory not only increases the risk of maladministration but also presents Queensland with a real opportunity to raise political standards…

“With its huge majority, the government could establish a new political paradigm simply by publicly acknowledging its limitations and committing itself to core ethical principles …

“However, self-interest makes it unlikely that political parties and politicians who benefit from the current system will initiate real change. That is a task for the community…”

Unfortunately, my pessimism was grossly optimistic. After 50 years as a barrister, 40 years next year as a QC, 35 years the following year since my first judicial appointment and 25 years since the corruption inquiry that led to political

and police reforms in Queensland, I’m not too easily surprised, but I remain unable to understand why a newly-elected government would want to return the State to its dark past or why a long-established newspaper, the Courier-Mail, which in the past supported attempts to keep Queensland governments honest, would support that folly.

Whatever the government’s reason for its conduct, populism provided it with camouflage. Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns” concept, “things we don’t know we don’t know”, underpins the populist approach, which treats voters as fools. People who don’t know that they don’t know are easy to persuade when they’re told what they want to hear, especially about emotive issues such as “law and order”.

Standard populist refrains build on envy and resentment to encourage ignorance and bigotry: educated people are “elites” who live in “ivory towers” and lack knowledge of the “real world”; evidence-based knowledge is inferior to intuitive “common sense” gained in a “school of hard knocks”; experts know less than a “table of wisdom” at the local pub; and judges, despite their oaths of office and obligations of impartiality and independence, should just do “what the people want”. Behind that populist facade, the government sacked, stacked and otherwise reduced the effectiveness of parliamentary committees, subverted and weakened the State’s anti-corruption Commission, made unprecedented attacks on the courts and the judiciary, appointed a totally unsuitable Chief Justice and reverted to selecting male judges almost exclusively, appointing 18 new male judges and magistrates but only 1 more to emerge; for example, concerning the inappropriate influence of politically supportive police.

Retired judges and lawyers who were shocked into criticising the government were disparaged for their effrontery.

The opinions of people who have spent their professional lives implementing an impartial legal system in accordance with the rule of law and grappling with the complex problems associated with criminal justice were patronisingly dismissed by the Premier and Attorney-General, neither of whom has the slightest knowledge or understanding of those matters. The Courier-Mail acted throughout as the government’s belligerent spear-carrier.

The current editor and his gossip-column cronies, who apparently regard dissent as insolent and “irritating”, demonstrated their contempt for democracy by attempting to stifle free speech by petulant name-calling and personal abuse, a tactic favoured by immature bullies everywhere.

Unsurprisingly, some who found their irrational opinions confirmed by populist rants and boorish invective joined in with vicious anonymous messages which revealed nothing beyond their inability to spell their vulgar vocabulary.

Political opposition to the government was restrained. Perhaps the other major party, the Australian Labor Party, which Queenslanders rejected less than three years ago, considered that its small parliamentary representation and the government’s resort to populism with Courier-Mail support made it prudent not to say too much in case it attracted attention to its own past conduct.

Nonetheless, the government’s unprincipled behaviour cost the Liberal National Party substantial support in recent by-elections. Ostensibly, it has modified its approach in the run-up to the forthcoming general election, but it hasn’t explained why it acted as it did or given any other sign that it is aware that it acted improperly or that it regrets the damage which it caused or the ongoing disharmony which it created within the State’s highest court. Similarly, the Labor Party has given no persuasive indication of a change of heart since its last term in government and that, if elected, it will exercise power solely for legitimate purposes.

The Preamble to the Constitution of Queensland 2001 recognises the fundamental premises of parliamentary democracy, namely that power is vested in the people who, in accordance with a “system of representative and responsible government”, elect representatives to exercise power on their behalf and in their interest. Subject to presently immaterial limitations, the elected Parliament can then enact any law. The assumption on which that doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty is based, that regular elections ensure that parliament only enacts laws which are for the State’s “peace welfare and good government”, is now neither valid nor even relevant in Queensland.

The political landscape today is radically different from that at the time when the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy was imported into Queensland in the nineteenth century. In practical terms, power has been substantially transferred to a small, cynical, political class, mostly professional politicians who represent, and act as directed by, one of the two major political parties which have entrenched themselves and their standards in the political system and collectively dominate political discussion and control the political process.

Modern politicians, who primarily see issues from a party perspective, regard the public interest as best served by their party holding power or at least by ensuring that the other major party doesn’t hold power. Politics is essentially merely a “no-holds-barred”, “win at all costs”, “whatever it takes” contest for power between the two parties. Every few years, the public is obliged to vote, knowing that one of the major parties will be elected and that it will use its power to benefit itself, the sectional interests which it represents and its financial supporters and ambitious camp-followers. In Queensland politico-speak, that’s “just the way the world works.”

It would not occur to today’s politicians that power should be used only for the State’s “peace welfare and good government” or that legal requirements are conventionally supplemented by ethical norms.

As matters stand, neither major party wants political standards to be a significant electoral issue and neither will willingly reform the flawed political process which they control and from which they each benefit. Government would first have to reform itself, which is impossible in institutions and organisations in which powerful vested interests oppose change.

Political reform is therefore a task for the community. If Queenslander’s want a free, fair, tolerant society, good governance and honest public administration, a sufficient number of voters must make it clear that they will decline to vote for any party which does not first satisfy them that it will exercise power only for the public benefit.

It’s difficult to perceive what legitimate reason a party seeking election in a democracy could have for declining to make commitments such as the following:

• the public to be fully and accurately informed promptly and not to be misled;

• all government decisions and actions to be taken for the common benefit without regard to personal, political or other considerations;

• all people to be treated equally with no person given special treatment or superior access or influence; and

• all public appointments to be made on merit.

Effective democracy needs principled politicians, an independent, impartial judiciary plus, as the American author Norman Mailer said, “individuals not only ready to enjoy freedom but to undergo the heavy labor of maintaining it.” That task includes blunt criticism of political misconduct. As President John F. Kennedy said, “without debate, without criticism no administration and no country can succeed and no republic can survive.”

It’s a lot to ask, but those who disagree with me might serve the public better by a reasoned explanation than just more spiteful bile.

Tony Fitzgerald, a former judge in the Federal Court of Australia between 1981 June 1984 and was the chair of the Commission of Inquiry into Official Corruption in Queensland between 1987 and 1989.

You can view the video of Tony Fitzgerald’s comments and the following Tony Fitzgerald Lecture 2014 lecture by US Professor David Bayley here. (Tony’s Fitzgerald’s comments appear a little after the 8 minute mark). The lecture was presented on Wednesday September 10, 2014.

E Carey

September 11, 2014 at 22:18

Thank you for publishing Tony’s whole speech, local Bris media only gave short quotes & (surprise, surprise) nothing on his brilliant & accurate critique of the Courier Mail. Things are grim in Queensland these days …

Gordon Bradbury

September 11, 2014 at 22:39

҉ۢ the public to be fully and accurately informed promptly and not to be misled;

• all government decisions and actions to be taken for the common benefit without regard to personal, political or other considerations;

• all people to be treated equally with no person given special treatment or superior access or influence; and

• all public appointments to be made on merit”.

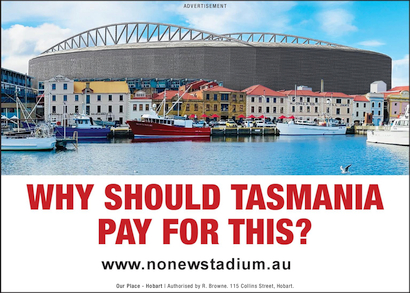

How about the Tasmanian community adopts these 4 political objectives also? Wouldn’t that cause a revolution?

Geraldine Allan

September 12, 2014 at 01:16

Bravo Tony Fitzgerald for saying it how it is.

#3, Gordon, I agree — these are simple but wise guidelines.

William Boeder

September 12, 2014 at 02:15

Based on the 4 principal objectives as stated by Tony Fitzgerald, the people of this State must now reject every facet of this State’s either Lib/Lab supposed right to rule.

Somewhere in and amongst Tasmania’s political system of today it seems quite obvious that there is no known endeavour to represent the people or even bother to serve the people that their elected status commands they must provide.

Again based on Tony Fitzgerald’s 4 points, where does this allow for a Senator, the likes of Eric Abetz, to be allowed a responsible State government appointment?

mike moore

September 12, 2014 at 11:26

I think Fitzgerald is incorrect. I believe the Courier Mail is actually worse than he says.. Mike Moore, Hervey Bay..

Mike Bolan

September 12, 2014 at 16:48

It speaks volumes when a person is congratulated for speaking out.

Such a result would be unnecessary in an open society or in a real democracy.

Real thinkers like Tony Fitzgerald are all too rare. Pressures of the media, unrepresentative political parties and cashed up global corporations are all combining to defeat free thinking and expression.

The mechanisms of fascism are all around.

Robert LePage

September 12, 2014 at 20:26

As you can see by the date this was my prediction for Queens land in 2012.

You should see what I said about abort but unfortunately I did not commit to paper or computer.

Prediction about Queens land for 2015

Save this letter and refer to it in three years time, because it will be spot on as a fulfilled prediction.

The People of Queens land will by then be really feeling the pain. Mining, Fracking, huge port building and displacing farms for mines will be getting into its stride.

There will be an influx of flyin/flyout workers that will be working for a lot less than their Australian counterparts used to.

Where feasible, even they will have been replaced by robot machinery to make even more profits for big business.

House prices will tumble because the workers who were paying off mortgages on high wages from Queens land mines will be out of work and no longer be able to service their loans.

A glut of houses will kill the housing market.

By then there will be most likely a further down turn in the World economy that will damp down the Chinese demand for minerals.

The Liberals will blame it on many years of Labour government.

What could the voters in Queens land have done?

Well vote for any alternative party to reduce the all-powerful mandate they have given the libnats. Yes even the Greens and Katter.

Too late now but keep it in mind for the next election.

Posted by Robert LePage on 26/03/12 at 09:52 AM

Bob Kendra

September 13, 2014 at 01:08

Mike Bolan is so frighteningly close to the truth! All has been rigged and rejigged for the coming opportunity to entrench rightwing government for the foreseeable future. All has been geared to maximise the rightwing surge flowing from another global conflict. All the signs are there. Once our fearless leaders don khaki full time we will be taken in head-first! Our TV and newspapers will revel in the headlines. Then there is no turning back. Three guesses: which politicians will be in their element?

Simon Warriner

September 13, 2014 at 11:13

re 10, what is even more frightening is that the labor party stands ever ready to receive the disillusioned masses and hand them straight back to exactly the same forces directing those right wing governments. Should the greens or any other party look like taking over labor’s mantle as the anointed opposition their leadership will be subverted and they will fall into line. That is how the system works.

Anthony John

September 13, 2014 at 18:08

The Empire Strikes Back !

Note Mr Fitzgerald’s observation that its unlikely political parties or politicians will initiate real change : that is a task for the community.

It was ever thus. But are we listening ? Ready to speak out fearlessly like he does against those in positions of power who would oppress, mislead and act corruptly?

Most of us unfortunately can find reasons why we cant speak out publicly, while raging privately. To little or no effect.

Tony

john hayward

September 13, 2014 at 21:31

What’s Fitzgerald complaining about?

Unlike Tas, Qld still has public eminences such as himself with the temerity and intellect to speak out against the gross debasement of public life by a political culture you would normally expect at a pro wrestling event.

Politics has become a kind of sporting competition where winners are decided by the outcome of bare-knuckle sledging contests. It’s not a game for the thoughtful and ethically squeamish.

Obtuse as he is, Abbott nonetheless spotted the trend when he applauded the rise of Rupert Murdoch as the referee of public taste as being one of the defining events in Australia’s history of human habitation.

The rise of Abbott himself could also be seen to herald the advent of coprophilia as the state religion.

John Hayward

Kim Peart

September 14, 2014 at 10:52

This is a time when the people of this nation need to stand as one for basic Australian values, such as a Fair Go and hammer what that means into our value system.

The Queensland parliament, lacking a higher house, swiftly reversed the onus of proof in law for a select group and potentially, for everyone, along with blocking our freedom to associate with any individual, which could be in the past.

Quite similar laws have appeared in Tasmania to target demonstrators, but having a higher house has applied the brake to the legislation.

Federally we see similar laws being applied to any individual who has visited any place that hits a select list, but our Senate may serve as a brake there.

With a divided national house, State authorities tend to copy each others authoritative tendencies.

The only way to turn this trend may be to get a higher house returned in Queensland and begin work on a national bill of rights, focusing on the meaning of a Fair Go.

The New Zealand Bill of Rights could serve as a good template this side of the Tasman.

I raised these matters in my two articles on the mad VLAD laws in the Tasmanian Times.

http://oldtt.pixelkey.biz/index.php?/article/the-fight-to-protect-our-rights-and-liberty/

http://oldtt.pixelkey.biz/index.php?/article/taken-for-a-ride/

Kim Peart